People Are NOT Your Greatest Asset. Their Skills Are, BUT Only When Applied to the Right Task at the Right Time.

Why most failed programs are resource allocation failures masquerading as execution failures, and what a precision operating model looks like.

Every major pharma organization uses some version of the same phrase: "aligning scientific capabilities with strategic priorities." GSK says it. Novartis says it. Roche says it. It appears in annual reports, investor presentations, and leadership town halls.

And it raises a question nobody asks.

If capability-to-priority matching is the acknowledged challenge, why does the entire industry solve it through template-driven, role-level, algorithmically approximate allocation rather than real-time, priority-driven, skill-based, task-level, named-person precision? Why do boards scrutinize capital allocation with quarterly rigor, while capability allocation gets annual planning cycles built on proxies, historical averages, and FTE estimates that no one fully trusts?

McKinsey's research on strategic workforce planning makes the asymmetry explicit: top-performing S&P 500 companies treat "talent with the same rigor as managing their financial capital." Those that do generate 300 percent more revenue per employee than the median firm. The implication is uncomfortable: most organizations do not apply that rigor. Capital gets quarterly forensic scrutiny. Capability gets proxy-based guesswork.

In 25 years of life sciences operations, I have watched the same post-mortem pattern unfold dozens of times. When a program underdelivers, organizations autopsy the strategy. The protocol. The timeline. The regulatory approach. They examine the science, the market assumptions, the competitive landscape.

They almost never examine the team.

Were the right people working on the right tasks at the right time? Not "did we have enough people," which is a headcount question. But were the specific capabilities on the team matched to the specific challenges the program faced at each stage? That question, the most consequential question in program execution, is the one least likely to be asked.

Most failed programs are resource allocation failures masquerading as execution failures.

This article is a forensic examination of how that happens: the mechanism by which talent allocation breaks down, the rational behaviors that sustain it, the downstream consequences that cascade from the mismatch, and what a precision operating model would look like.

The Trilogy That Got Us Here

The thesis builds on two provocative arguments that preceded it.

Jeffrey Pfeffer, the Thomas D. Dee II Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, has spent decades exposing the hypocrisy: organizations call people their greatest asset, then make them the first line item cut in a downturn. His advice to laid-off workers is blunt: when a company tells you people are their most important asset, check whether that belief holds when times get tough. For most, it does not. The platitude dissolves at the first sign of financial pressure.

Bradley and McDonald in Harvard Business Review, drawing on Gartner research, advanced the argument: people are not your greatest asset. The right people, empowered in the right roles, are. Mere presence is not value. Fit is.

And yet. Deloitte's skills-based organization research, surveying over 1,200 professionals, found that 30% of organizations are still ineffective at matching the right talent to work. The insight was published. The industry acknowledged it. And then it continued doing exactly what it had always done.

This article completes the trilogy. It is not even empowerment in the abstract. It is the precision of matching specific capabilities to specific needs at specific moments. Not "the right people." The right person, on the right task, at the right time.

The distinction matters because it shifts the conversation from philosophy to operations. From "do we value our people?" to "do we know, right now, whether the person executing this $150M program's most critical deliverable is the best-suited person we have for that specific challenge?"

As we explored in Headcount Is Not Capability, the industry's reflexive response to operational problems, adding headcount during growth and cutting during downturns, confuses bodies with coordination. This companion piece goes deeper: into the mechanism itself. How does allocation actually work? Where does precision break down? And why do rational people perpetuate a system that everyone quietly acknowledges is broken?

Template Fiction: Where the Demand Signal Gets Distorted

The allocation mechanism in pharma operates as a three-step chain. Each step introduces distortion that the next step inherits and compounds.

It starts with demand generation. And it starts at the wrong altitude.

Historical project archetypes drive algorithmic FTE estimation. "What functions, roles, and headcount did similar projects use?" becomes the demand signal. If the last Phase III oncology program required 14 regulatory FTEs, the model assumes 14 regulatory FTEs for the next one. The approach is fast, algorithmically elegant, and embedded in most enterprise resource planning systems.

It also encodes a fiction.

Nobody builds a prospective work breakdown structure before calculating demand. Nobody asks: what are the specific work packages this program needs to execute, in its current circumstances, with its current risk profile, and in the potentially evolving conditions ahead? Instead, demand is calculated at the highest level of abstraction: program-level FTEs, derived from historical templates, applied to programs that bear surface resemblance to predecessors but share little of their underlying complexity.

A first-in-class biologic with a novel mechanism of action and a pediatric indication is not interchangeable with a follow-on small molecule in the same therapeutic area. But the demand generation engine treats them as functionally equivalent because the template says "Phase III Oncology."

The industry is beginning to recognize this. Some organizations are moving from program-level FTE planning to function-level and role-level demand. A few are beginning to surface named resources rather than anonymous FTE slots. But even these advances remain FTE-denominated, role-level approximations. Skill-based, task-level, named-person resourcing, where demand is generated from a prospective work breakdown structure and fulfilled by the specific individual whose skills, experience, availability, and capacity best match the work at the expected point in time, remains on the horizon for most top-20 pharma companies.

The correct sequence is the inverse of current practice. Start with the work: build prospective work breakdown structures for each program based on its actual scope, complexity, and risk profile. Derive skill-based, task-level demand from that structure. Then fulfill that demand with named individuals matched on skill fit, relevant experience, current availability, and projected capacity at the point of execution. Not "14 regulatory FTEs." Rather: these seven specific regulatory deliverables require these four specific regulatory capabilities, and here are the three named individuals best positioned to execute them in Q3.

World Pharma Today confirms that traditional pharma resource planning follows annual cycles that produce "systematic inefficiencies," with some functions perpetually underutilized while others are perpetually understaffed. Neither of the two dominant planning approaches, the publication found, adequately addresses modern portfolio complexity.

The demand signal arrives pre-distorted. And everything downstream inherits the distortion.

Availability Over Fit: The Matching Problem

The guesstimated demand flows to functional leaders and resource managers who match available people to templated roles. Here, a second distortion enters.

The question asked is "who is available when?" not "who has the right skills, relevant experience, and expertise for this specific work?"

And critically, even when the right person exists but is assigned elsewhere, nobody asks: should they be reassigned because this program is higher priority, better suited to their skills, and more consequential to the portfolio?

Three proxy mechanisms substitute for genuine fit, and they operate at every level:

Availability is the default. Who happens to be free when the slot opens becomes the primary selection criterion. Not who is best suited. Who is unbooked.

Org chart inheritance determines scope. "You are in the oncology team, so you work on oncology programs." As we documented in Four Companies Wearing One Logo, functional boundaries are architectural, not accidental. Those same boundaries dictate talent assignment, regardless of whether the specific challenge matches the specific person's strengths.

Manager networks shape opportunity. The person who gets the career-defining assignment is often the person whose manager has the strongest relationship with the hiring VP. Not necessarily the person whose capability profile is the best match for the challenge.

The result: in any given week across a portfolio of hundreds of programs, the best-suited people are rarely working on the most closely aligned tasks. The matching is approximate at best, random at worst.

And then the compounding begins.

Initial proxy assignments are never revisited. A program that started in clinical execution mode shifts to regulatory strategy mode six months later, but the team composition remains frozen at the original match. The person assigned because they were available during study startup is still assigned during the submission sprint, even though the work has fundamentally changed and their skill profile no longer fits the program's most critical needs.

Multiply this across every program in the portfolio. Each phase transition introduces new mismatches layered on top of old ones. A team that was 70% fit at assignment becomes 50% fit after the first pivot and 30% fit after the second. Nobody measures this erosion because nobody re-evaluates team composition against evolving program demands. The original proxy bet, made once, under time pressure, with incomplete information, becomes the permanent operating reality for the life of the program.

Distorted demand feeds proxy matching. Proxy matching compounds over time. And the compounding is invisible because the system has no mechanism for reassessment.

Why Proxies Win: The Self-Reinforcing Loop

The three-step chain, template demand, proxy matching, compounding effect, is not a design flaw. It is the inevitable outcome of a system optimized for filling slots rather than matching capabilities.

Proxies persist because precision is expensive and uncomfortable. Matching by availability takes a day. Matching by specific capability takes weeks, requires skills data that does not exist in most organizations, and might surface the uncomfortable truth that the organization lacks the right person entirely. The proxy path is faster, less politically fraught, and produces an answer that looks adequate on paper.

The pattern is invisible because there is no counterfactual. The cost of proxy allocation does not appear in any dashboard. It surfaces as slower timelines, more cautious decisions, more rework, more surprises. All of which get attributed to "complexity" or "the nature of drug development" rather than traced to their origin: team composition.

The same organizations that apply forensic rigor to molecule selection, protocol design, and capital allocation accept approximate-at-best matching for the humans executing $50M to $200M+ programs.

The allocation mechanism has never been examined as a mechanism. It is treated as an administrative process, not a strategic one.

The Dynamics That Sustain the Machine

If the system is broken, why do rational people perpetuate it? Because the behavioral incentives are perfectly aligned to sustain it.

Manager self-interest is the first dynamic. A manager who "lends" their best person to another program loses capacity with no reward. So they protect their talent and offer their least critical people when asked to share resources. The best people stay on the manager's own projects. The portfolio gets the leftovers.

The visibility penalty is the second. If you are known to have spare capacity, you get loaded up. So people and managers obscure availability. They pad allocations. They resist transparency. Not because they are gaming the system, but because the system punishes those who reveal slack.

The interchangeability assumption is the third. "We need a project manager" is a request that takes a day to fill. "We need the person who has managed CMC timelines through PAI inspection windows with our European CMO partners" is a request that might take weeks, and might force the uncomfortable admission that you do not have that person. Organizations default to the simpler request because it produces faster, less disruptive answers.

Seniority-as-proxy is the fourth. Deloitte's research found that only 12% of organizations practice long-term strategic workforce planning. In the absence of skills data, organizations substitute hierarchy for precision. "A Senior Director must be good at everything a Senior Director should do, right?" The title becomes the only data point in the matching algorithm.

And governing these dynamics is the structural gap that makes them invisible: portfolio review committees scrutinize timelines, budgets, milestones, and risks. They almost never ask: "Is the right team assembled for this specific phase of this specific program?"

There is a committee to approve $50M in program spend. There is no equivalent committee verifying that the team executing that spend has the specific capabilities required. Steering committees approve program plans. They do not approve team compositions. Resource allocation committees, where they exist, deal in headcount numbers, not named-person-to-task matching.

McKinsey and ISPE found that only 40% of pharma companies believe they know which skills they need now. Less than 25% can project future needs. The data infrastructure to even ask the matching question does not exist in most organizations.

Three Cascades Nobody Traces Back

The matching failure cascades into three operational domains, and each one is rarely connected to its origin.

The first cascade is distorted hiring. Companies over-hire because they cannot see that they already have the right talent trapped on the wrong programs. The demand signal to recruiting is inflated by misallocation. They hire for gaps that are actually internal deployment failures. The industry's accelerating shift to contract hiring, a structural pivot visible across BioSpace workforce data, is partly the market bridging capability gaps externally that could be solved by internal reallocation, if anyone could see the internal landscape clearly enough.

The second cascade is simultaneous surplus and shortage. Without visibility into what programs actually need versus what is assigned, portfolios experience overstaffing and understaffing at the same time. Some programs carry profiles that do not match their current challenges, while critical programs starve for the specific expertise they need. This is the "systematic inefficiency" that World Pharma Today identified: perpetual underutilization in some functions running alongside perpetual understaffing in others.

The third cascade is capability blindness. The organization loses the ability to know what it is capable of, because the mapping between talent and work is so opaque that strategic workforce planning becomes guesswork. You cannot match what you cannot see.

Compounding all three is the invisible opportunity cost. Put the wrong people on the wrong work and you do not just lose their time. You lose the compounding value of what the right person would have produced. A program managed by someone who has navigated this exact complexity before moves faster, anticipates problems earlier, makes better decisions at each fork. A program managed by someone available but inexperienced produces competent but slower, more cautious, less creative output.

The delta between these two outcomes is almost invisible because nobody measures the gap between "what we got" and "what we could have gotten." But over months and years, across hundreds of programs, the compounding cost is staggering.

The Jockey, Not the Horse

If the argument above sounds theoretical, consider how the world's most rigorous capital allocators think about team composition.

Gompers, Gornall, Kaplan, and Strebulaev surveyed 885 venture capitalists across 681 firms (Journal of Financial Economics). The findings are stark: 95% cite team as an essential factor in investment decisions. 47% rank it the single most important factor, above business model, product, and market. When asked what most contributed to both success and failure of their investments, team was the dominant answer, cited by 96% for successes and 92% for failures.

The companion research from Kaplan, Sensoy, and Stromberg deepens the point: in VC-backed companies that succeed, the strategy changes more often than the team. The team is the more stable predictor of outcomes. Investors call this the "jockey over horse" principle. Bet on the team, not the plan. Plans change. The right team adapts.

Now consider the implication.

VCs apply this rigor to $2M seed investments. Pharma makes $50M to $200M+ program bets with less scrutiny on team composition. A VC partner conducting due diligence on a Phase III program team would be startled, not by the science, but by the absence of any systematic assessment of whether the people executing a $150M bet are the right people for that specific bet.

The governance gap between how pharma allocates capital and how it allocates capability is not a minor oversight. It is a structural blind spot at the center of program execution.

From Slot-Filling to Capability Orchestration

The diagnosis above identified three specific failures: fictional demand signals, proxy-based matching, and static allocation that is never revisited. The reframe must address each one.

The core shift is from "do we have enough people?" to "are the right capabilities applied to the right challenges at the right time?" Capability is only an asset when it is available and matched to the specific need at the specific moment. A brilliant CMC scientist overallocated across three programs is not a capability. They are a bottleneck.

This shift operates on three pillars.

The first pillar is what the system must answer in real time. The current system answers one question: "Is this role filled?" The operating model must answer six: Who is working on what, at what capacity, right now? What specific capabilities does each person bring, beyond their title? What does each program's current phase specifically require? Where is the mismatch between what is assigned and what is needed? Who in the portfolio is better suited to this challenge than the person currently assigned? And when will the program's needs shift, requiring different capabilities?

These are not theoretical questions. They are the questions a VC partner would ask about any investment. Pharma does not ask them because the infrastructure to answer them does not exist, and the governance to act on the answers does not exist either.

The second pillar is governance reform. Portfolio reviews must expand from headcount sufficiency to team composition quality. The committee that exists for capital allocation, examining whether each dollar is deployed to its highest-value use, must have its equivalent for capability allocation. Team-to-challenge fit must be reviewed continuously, not assigned once at program start and left static for years. As explored in The Coordination Fallacy, plans that are never revisited become compliance artifacts rather than working tools. The same is true of team assignments.

And the incentive structure must flip. A manager who deploys their best person to a higher-priority program currently loses capacity with no reward. The governance model must recognize and reward talent deployed to highest-value work across the portfolio, not just within a single function's boundaries.

The third pillar is the cultural substrate. Language shapes possibility. "I have 12 people" is a headcount statement. "I have these specific capabilities available at these times" is a matching statement. When leaders describe their teams in terms of named capabilities rather than numbers, the conversation about precision becomes possible. "Lending" talent implies loss. "Deploying" capability implies precision. The framing determines whether cross-functional talent sharing feels like sacrifice or strategic optimization.

Breaking the seniority-as-proxy assumption requires skills data infrastructure: not self-reported inventories, which are universally unreliable, but observed capability profiles built from actual project histories. What has this person done? On what kind of challenges? With what outcomes?

If you get the matching right at the task level, if you know who will do exactly what and when, and that they have the right experience and bandwidth for that specific assignment, you do not need to worry about how the task will be done. You have trust. And trust makes oversight unnecessary.

The direction is clear. Deloitte's 2026 Life Sciences Outlook found that only 22% of biopharma organizations have successfully scaled even basic AI tools for workforce productivity, while 29% plan to adopt them. The technology direction exists. Multiple analysts point toward dynamic, real-time capability orchestration as the next frontier. The practice in pharma does not yet exist.

The question is not whether this level of precision is achievable. It is whether the cost of imprecision, compounding invisibly across hundreds of programs, remains acceptable.

The Question That Matters Most

Pfeffer exposed the hypocrisy of the "people are our greatest asset" platitude. HBR advanced the argument to "the right people, empowered in the right roles." This analysis completes the trilogy: it is not even empowerment in the abstract. It is the precision of matching specific capabilities to specific needs at specific moments.

When a program goes sideways, the variables that get examined are the ones that have dashboards: timelines, budgets, milestones, regulatory interactions. The variable that almost never gets examined is the one with the most predictive power: who was actually on the team?

Were the right people working on the right problems at the right time?

Until organizations can answer that question with data rather than assumptions, the most expensive resource in life sciences, specialized human expertise, will continue to be deployed with less precision than a seed-stage venture investor applies to a $2M bet.

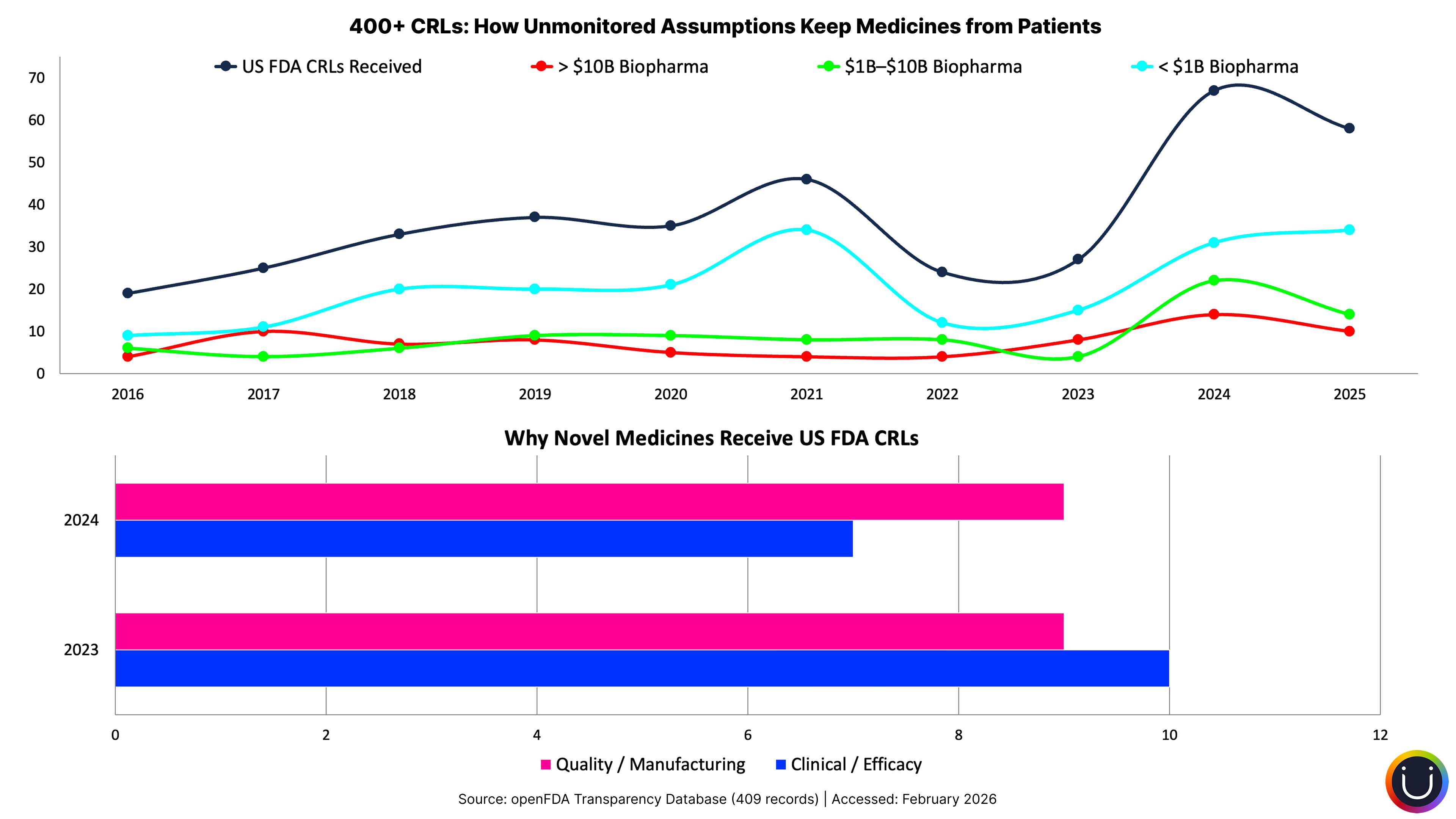

The governance gap between capital and capability is not an HR problem. It is not a technology problem. It is a patient access problem. Every capability mismatch adds friction. Friction adds months. And months added to development timelines are months that patients wait for medicines that already exist in laboratories but have not yet reached the people who need them.

The committee that approves $50M in program spend already exists. The equivalent committee, the one that verifies the team executing that spend has the specific capabilities required, does not.

What would it take to build it?

As The Buffer Illusion warned, accelerated regulatory timelines are eliminating the coordination buffers that organizations have relied on for decades. The margin for imprecision in how we deploy human capability is shrinking. The organizations that figure out precision matching, that move from slot-filling to capability orchestration, will not just execute faster. They will compound advantage with every program, every quarter, every governance cycle.

The question that matters most is the one almost never asked at program reviews: is the right person working on the right task at the right time?

References

- McKinsey & Company, "The Critical Role of Strategic Workforce Planning in the Age of AI." Revenue per employee in top-performing S&P 500 companies.

- Jeffrey Pfeffer, Stanford Graduate School of Business, "Why Copycat Layoffs Won't Help Tech Companies or Their Employees." The hypocrisy of the "people are our greatest asset" platitude.

- Bradley and McDonald, Harvard Business Review, "People Are Not Your Greatest Asset." The right people, empowered in the right roles, are.

- Deloitte, "Building Tomorrow's Skills-Based Organization." 30% of organizations ineffective at matching talent to work.

- World Pharma Today, "Smarter Resource Planning for Complex Pharma Development Portfolios." Systematic inefficiencies in traditional planning approaches.

- Deloitte, "Skills-Based Hiring and Organizational Design." Only 12% of organizations practice long-term strategic workforce planning.

- McKinsey and ISPE, "Pharma Operations: Creating the Workforce of the Future." Only 40% of pharma companies believe they know which skills they need now.

- BioSpace, "7 Key Insights into the 2026 Job Market and Hiring Landscape." Industry shift to contract hiring as a structural response to capability gaps.

- Gompers, Gornall, Kaplan, and Strebulaev, "How Do Venture Capitalists Make Decisions?" Journal of Financial Economics. 95% cite team as essential; 47% rank it the single most important factor.

- Kaplan, Sensoy, and Stromberg, "Should Investors Bet on the Jockey or the Horse?" NBER Working Paper. Strategy changes more often than team in successful ventures.

- Deloitte, "2026 Life Sciences Outlook." Only 22% of biopharma organizations have scaled AI tools for workforce productivity.

Further Reading

- Headcount Is Not Capability: Why Pharma Keeps Hiring and Firing Its Way to the Same Problem

- Four Companies Wearing One Logo: The Architecture of Disconnection

- The Coordination Fallacy: Two Realities in Drug Development

- The Buffer Illusion: When Faster Approvals Expose Slower Organizations

Compliance

Unipr is built on trust, privacy, and enterprise-grade compliance. We never train our models on your data.

Start Building Today

Log in or create a free account to scope, build, map, compare, and enrich your projects with Planner.