"Of Course..." How Assumptions Fail Programs at Predictable Inflection Points

Late-stage trial terminations doubled from 11% to 22%. The driver? Not bad science. Bad assumptions. Every program has a Gantt chart. Few have an assumption map.

When Bones Break and Assumptions Don't

On December 29, 2025, Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical announced results from two Phase III trials testing setrusumab in osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic disorder that causes fragile bones.

The bone density data looked good. In both the ORBIT and COSMIC studies, patients showed statistically significant improvements in bone mineral density. This was consistent with the Phase II results that had justified the investment in pivotal trials. The science, by the measure everyone had been tracking, was working.

Then came the primary endpoint. Fracture rate. The measure that mattered to patients and regulators alike. And setrusumab didn't move it. Not in children aged 5 to 25. Not in children aged 2 to 6. Not against placebo. Not against bisphosphonates.

Ultragenyx's stock dropped 43% in a single day. One billion dollars in market value, gone. Its European partner Mereo BioPharma fell 88%, entering penny share territory. Both companies announced immediate cost-cutting measures.

Here is what makes this story worth examining beyond the headlines. The Phase III readout was a known milestone, on every timeline, every investor deck, every Gantt chart for years. There was nothing surprising about the moment itself. What was surprising was what the team discovered when they arrived at it: a door they expected to be open was locked.

The assumption that bone density improvement would translate to fracture reduction had been foundational since the program's earliest stages. It was reasonable. It was based on the mechanism of action (sclerostin inhibition increases bone formation). It was consistent with mouse models showing increased bone strength. And at least one analyst had publicly questioned it: Truist Securities noted that "alas, more defective bone does not result in stronger bone." Yet the program committed to pivotal trials with fracture rate as the primary endpoint without independently validating that foundational link in human patients.

After twenty years in pharmaceutical operations, building systems that help organizations coordinate the staggering complexity of drug development, I've watched this pattern more times than I can count. Not this specific failure. This specific dynamic: a predictable moment arrives, an unmonitored assumption surfaces, and teams discover they have fewer options than they thought. The Ultragenyx case involved a scientific assumption that arguably couldn't be fully tested until Phase III. But the same dynamic plays out in operational domains, manufacturing, regulatory, competitive, enrollment, where the assumptions can be verified, the evidence is available, and the cost of checking is a fraction of the cost of being wrong.

The Ultragenyx story is dramatic because the market impact was immediate and public. But the same dynamic plays out quietly inside pharmaceutical programs every month. And the cost, measured in months of delay, dollars burned, and patients waiting, is enormous.

An Inflection Point Without a Valid Assumption Is Just a Surprise

Every drug development program has a handful of moments where the path forward can diverge. These aren't crises. They aren't black swan events. They are known, predictable inflection points that appear on every program's timeline from Day 1.

Phase II readout: Does the efficacy signal justify pivotal investment? Regulatory feedback: Does the agency agree with the development plan? Manufacturing feasibility: Can the process scale from clinical supply to commercial production? Competitive entry: Has a competitor changed the treatment landscape? Payer signal: Will the health economics support the pricing thesis?

These moments are on every Gantt chart. They show up in every governance review. Program teams discuss them. Leadership monitors them. In one important sense, they are the most visible milestones in any development program.

And yet.

Teams arrive at each one without having identified the assumptions that determine which options are available when that moment hits. The inflection point is on the calendar. The assumption beneath it is not.

Every program has a Gantt chart. Almost none have an assumption map.

The distinction matters because inflection points are not milestones in the traditional sense. A milestone says "we will have Phase III data by Q3." An inflection point says "when we have Phase III data, the path will fork, and the fork we can take depends on a set of conditions we are currently assuming will be true."

"Of Course": Two Words That Hide Risk in Plain Sight

These invisible assumptions share a tell. They tend to begin with two words: "of course." Of course the manufacturing process will scale. Of course the regulatory pathway won't shift. Of course the surrogate endpoint will translate. The phrase signals an assumption so foundational that nobody classifies it as a risk. And that is precisely what makes it dangerous.

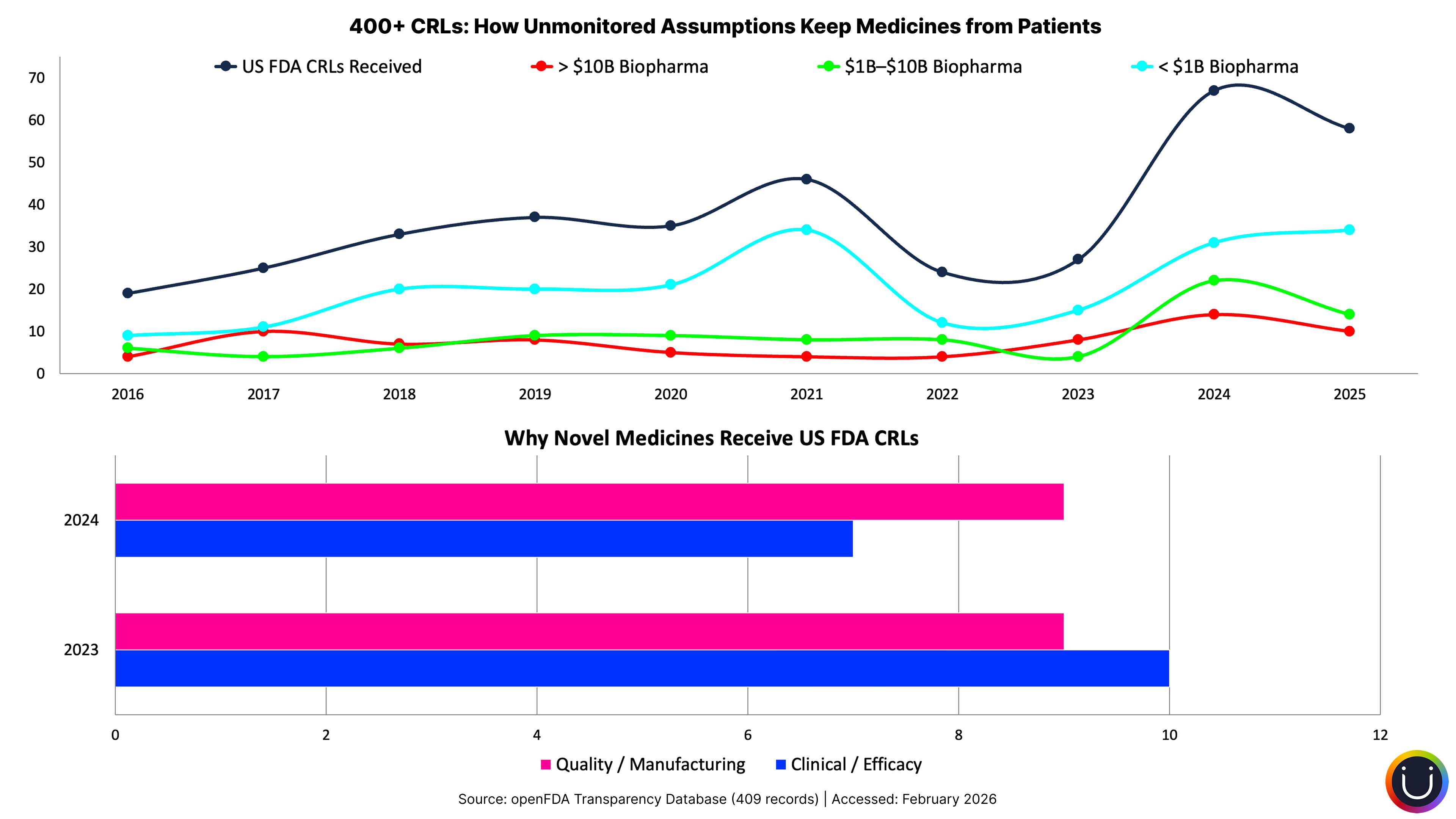

When the FDA published more than 200 Complete Response Letters for the first time in July 2025, the analysis revealed something striking: 74% of those rejections cited quality or manufacturing deficiencies. Not safety signals. Not efficacy failures. Manufacturing.

Beneath every one of those rejections lies an assumption made years earlier: "Of course the manufacturing process will scale to commercial requirements." That assumption was set at program initiation, documented in early feasibility assessments, and then buried under years of clinical milestones, regulatory interactions, and portfolio reviews. The filing, a predictable inflection point on every program's timeline, arrived. And the manufacturing assumption had quietly become false.

As we examined in The Buffer Illusion, the coordination challenges behind these manufacturing gaps are structural, not accidental. But the mechanism through which they damage programs is specific: an assumption made at one point in time goes unmonitored until the moment it matters most.

The same pattern repeats across four categories of assumptions that tend to go unverified for years:

Manufacturing scalability. "Of course the process will transfer to commercial scale." Yet 74% of CRLs say otherwise. For the gene and cell therapy sector, the gap is even starker: about 40% of INDs are being stopped or not accepted due to CMC issues. As one industry consultant noted, many biotechs prioritized early clinical milestones over manufacturing maturity, deferring CMC planning until proof of concept. The assumption was deferred, not monitored, and it broke at the filing inflection point.

Regulatory pathway stability. "Of course the guidance won't change mid-development." Programs that take 7 to 12 years routinely face regulatory landscapes that have evolved substantially since their IND filing. The accelerated approval pathway is a case in point: dozens of programs built regulatory strategies around it, only for the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act to grant FDA new authority to require confirmatory trials before approval and expedite withdrawals. Within two years, Pfizer's Oxbryta, Biogen's Aduhelm, and Takeda's Exkivity were all pulled from the market. The pathway assumption those programs were built on shifted beneath them mid-stride.

Competitive landscape. "Of course we'll still be first-to-market in five years." The obesity market has transformed around programs that spent years developing therapies based on competitive assumptions that semaglutide and tirzepatide rendered obsolete. The competitive entry inflection point arrives, and the assumptions about market position have silently broken.

Patient population access. "Of course enrollment assumptions from the protocol will hold." The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development found that 80% of Phase III protocols require an average of 3.5 substantial amendments, with implementation taking 260 days per amendment. What is a protocol amendment, operationally? It is the formal acknowledgment that an assumption made during protocol design has proven false. The eligibility criteria were too restrictive. The regulatory agency requested changes. The clinical strategy shifted. Each amendment is an assumption failure that became visible at an inflection point. And since protocols requiring amendments see enrollment timelines nearly three times longer than those without, the cost compounds rapidly.

Each is reasonable when first stated. Each can become false during a development timeline measured in years. And each tends to surface only when the program reaches the inflection point where that assumption determines the available options.

From 11% to 22%: When the Science Works but the Assumptions Don't

The scale of this problem is difficult to dismiss as anecdotal.

A January 2026 analysis published in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery examined 3,180 terminated clinical trials over a decade and found that late-stage termination rates have doubled, from 11% to 22%. That finding alone would be significant. But what makes it remarkable is the shift in why programs terminate. The leading driver of Phase II and III terminations is no longer efficacy failure. It is strategic and business decisions. Companies aren't just discovering that the science didn't work. They're discovering that the assumptions beneath their strategic choices, about competitive positioning, about market dynamics, about regulatory feasibility, no longer hold.

The trend is accelerating, not stabilizing. Amendment volume has increased nearly 60% over seven years. Sites now operate under different protocol versions for an average of 215 days. One in four amendments is implemented before the first patient visit, meaning the assumption failed before execution even started. The Tufts researchers note that 23% of amendments are preventable through better planning and design. An older study put the preventable rate at 45%. These are not unknowable risks. They are knowable assumptions that nobody is systematically verifying.

The patient cost is the one that matters most. Every amendment adds an average of 260 days to a program timeline. Every CRL adds 12 to 18 months. Every scramble to develop a Plan B that should have been pre-positioned adds time between a promising therapy and the patients who need it.

The business cost is the one that makes the case for change. Ultragenyx lost $1 billion in market value in a single day. Protocol amendments cost upward of $500,000 each in direct costs, not counting the enrollment delays. The uncomfortable truth: none of this is surprising in retrospect. The inflection points were on the calendar. The assumptions were identifiable. What was missing was anyone watching the space between the two.

The Assumption Nobody Questions: That Assumptions Don't Need Questioning

If the inflection points are predictable and the assumptions are identifiable, why does this gap persist?

Structurally, no role or process exists specifically for monitoring assumption validity. Risk registers track identified risks. Milestone trackers monitor progress against the plan. Governance reviews ask "are we on track?" Nobody asks "are the assumptions that make our plan meaningful still true?"

The tools to ask that question exist. The FDA itself published guidance on adaptive trial designs that build decision points into clinical programs. Yet as STAT News reported, "complexity often creates a barrier to widespread adoption," with adoption rates around 22%. Even at the individual trial level, building in structured decision flexibility remains the exception. At the program strategy level, where the manufacturing assumptions and competitive assumptions and regulatory assumptions live, it is virtually absent.

As we explored in The Coordination Fallacy, plans in pharmaceutical organizations tend to become compliance artifacts rather than living working documents. Once the plan is approved through governance, it becomes a commitment. And commitments, by their nature, resist questioning.

This creates a behavioral dynamic that compounds the structural gap. In most pharmaceutical organizations, scenario planning is perceived as a lack of commitment rather than prudent planning. Raising "what if this assumption turns out to be wrong?" is heard as "I don't believe in the plan." If you're already thinking about Plan B, you must not believe in Plan A.

The consequence asymmetry is revealing. Question an assumption early and you're perceived as the pessimist who lacks confidence. The assumption fails at the inflection point and the team scrambles, but "nobody could have seen it coming." The organizational math favors silence: don't question, don't monitor, and if the assumption breaks, share the collective surprise with everyone else.

What doesn't exist is the cultural permission to treat assumptions as hypotheses rather than commitments.

Assumptions Are Hypotheses Dressed as Facts

What would it take to close this gap?

Not a new system. Not a new committee. Not another layer of governance. Programs already have more governance than most teams can absorb.

What's needed is a shift in how programs think about the foundation beneath their plans. From treating plans as commitment documents, where assumptions are set at initiation and never revisited, to treating them as hypothesis maps, where the critical assumptions beneath each inflection point are explicitly named, owned, and periodically verified.

As we explored in Four Companies Wearing One Logo, functional fragmentation means that assumptions about manufacturing live in one organizational compartment while assumptions about clinical strategy live in another. The clinical team assumes the manufacturing process will scale. The manufacturing team assumes the clinical data will support the filing. Each function holds assumptions about the others, and nobody maps the dependencies between them.

Here's a starting point any VP of Portfolio or Program Management can apply next Monday morning. Pick one program. Map its next three inflection points, the moments where the path forward can diverge. For each, list the assumptions that determine which options will be available when that moment arrives. Ask: when was the last time anyone verified that each assumption is still true? For any assumption older than 12 months without verification, that's your exposure.

This takes an afternoon, not a transformation initiative. And it will surface gaps that no amount of milestone tracking or governance review will reveal.

Milestone tracking tells you whether the program is on time. Assumption mapping tells you whether "on time" still means what you think it means.

The challenge isn't doing this exercise once. It's building the discipline to do it continuously, across a portfolio of 30 to 50 active programs, each with five to seven inflection points, each with three to five underlying assumptions. Quarterly reviews and spreadsheets cannot sustain that scope. The organizations that close this gap will be the ones that monitor their assumption landscape with the same rigor they apply to their milestone landscape: continuously, systematically, and with the expectation that some assumptions will change.

Uncertainty Is Inevitable. Ignorance Is Optional.

There is a difference between uncertainty and willful ignorance. Uncertainty is not knowing whether your drug will work. Willful ignorance is not knowing whether the assumptions beneath your program are still true, when you could know, if anyone were looking.

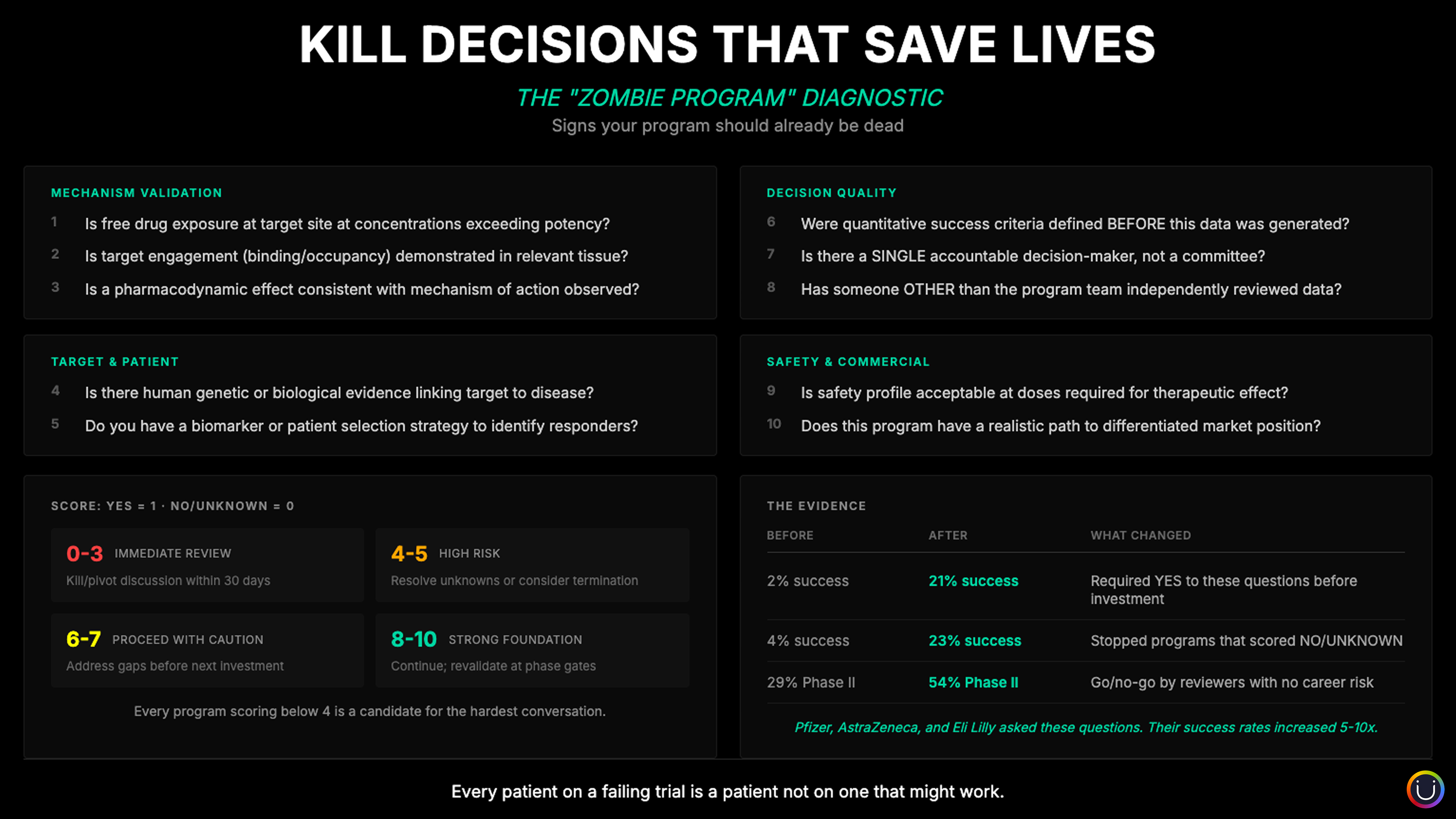

The kill decision, as we explored in The Kill Decision Problem, is one inflection point in a much larger landscape. Most forks in drug development aren't kill-or-continue decisions. They're which-path-forward decisions. And the quality of those decisions depends entirely on whether the options you thought you had are still available.

Every program has a handful of moments where the path forks. And at every fork, there's an assumption nobody is watching that determines which roads are still open.

The inflection points are already on every calendar. The assumptions are already in every team's head, often unspoken. The question is whether your organization treats those assumptions with the same discipline it treats milestones. Whether "of course" is challenged with the same rigor as "on track."

Every program in your portfolio has forks ahead. And at every fork, there is an assumption that will determine which doors are still open when you arrive. The organizations that don't just map but proactively track those assumptions choose their path. The ones that don't discover it.

References

- Getz, K. et al. (2024). "Protocol amendments and their impact on clinical trial performance." Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science.

- Pharma Manufacturing (2025). "FDA's CRLs reveal 74% of applications rejected for quality/manufacturing issues."

- FierceBiotech (2026). "Ultragenyx plans major cost-cutting push after flunking Phase 3 brittle bone trials."

- BioSpace (2026). "Ultragenyx loses $1B in market value as bone drug fails to reduce fractures."

- Getz, K. (2023). "Shining a light on the inefficiencies in amendment implementation." Applied Clinical Trials.

- Epistemic AI / Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2025). Analysis of 3,180 terminated clinical trials (2013-2023).

- STAT News (2024). "Adaptive trial designs increase speed, safety, effectiveness."

- Drug Discovery News (2025). "Why gene and cell therapies are stalling at the FDA."

Further Reading

- The Life of a Drug Is Short. Make Every Day Count. On why every month of development delay shortens commercial exclusivity, and why time is the scarcest resource in pharmaceutical development.

- Headcount Is Not Capability: Why Pharma Keeps Hiring and Firing Its Way to the Same Problem. On why adding resources doesn't solve structural problems, and the difference between ownership and assignment.

- Multibillion Dollar Portfolio Decisions: When Guesstimates Aren't Enough. On portfolio decision frameworks and the scale of investment at stake when assumptions go unexamined.

- The $25B AI Paradox: Why Pharma Is Missing Its Biggest Opportunity. On risk asymmetry and why organizations avoid operational transformation even when they know it's needed.

Compliance

Unipr is built on trust, privacy, and enterprise-grade compliance. We never train our models on your data.

Start Building Today

Log in or create a free account to scope, build, map, compare, and enrich your projects with Planner.